A casual reader of one of the major texts in linguistic theory, Kayne (1994), may be struck by the statement that “reverse German” does not exist. Let us for the moment choose to ignore what Kayne actually meant by that statement. Instead, let us focus on the fact that the statement, as it stands, is bound in itself to awaken curiosity. What kind of a language would reverse German be? Or to localize the question more closely to Lund, what kind of a language would reverse Swedish be? If reverse Swedish (let us call it Dews-ish) exists, what properties would it have?

It all depends what we look at. Let us deliberately refrain from looking at what Kayne meant, and investigate some other parameters. One suitable example would be the realization of the definiteness distinction.

In Swedish, definiteness is indicated by a suffix on the noun (1a), while indefiniteness is indicated by an indefinite article preceding the noun (1b). In Arabic, the exact opposite occurs: definiteness is marked by a definite article preceding the noun (2a), while it is indefiniteness which sports the suffix (2b). The fact that the Arabic indefiniteness suffix –n appears identical to one of the forms of the definiteness suffixes in Swedish is an extra quirk: does it make Arabic more or less a reverse mirror image of Swedish?

1a) flicka-n 1b) en flicka

girl-DEF INDEF girl

‘the girl’ ‘a girl’

2a) ᵓal-fatɑ̄tu 2b) fatɑ̄tu-n

DEF-girl girl-INDEF

‘the girl’ ‘a girl’

In fact, Arabic also serves as another example of reverse Swedish: in Swedish, the gender of the noun is reflected on the article with which it occurs, but not on the verb of which it is the subject. In Arabic, the article is identical regardless of the gender of the noun, but the verb agrees with its subject in gender (3a, b).

3a) nɑ̄m-a ᵓal-walad-u

slept-3S.M DEF-boy-NOM

‘The boy slept.’

3b) nɑ̄m-a-t ᵓal-fatɑ̄t-u

slept-3S-F DEF-girl-NOM

‘The girl slept.’

So perhaps Arabic truly is reverse Swedish? Not if we look at noun phrase word order: For instance, in Arabic, as in Swedish, the relative clause follows the noun (4a, b).

4a) ᵓal-fatayat-u [allatī katabna ᵓal-risɑ̄lat-a ]

DET-girl.PL-NOM [REL.FEM.NOM wrote.FEM.PL DET-letter-ACC]

‘the girls who wrote the letter.’

4b) flick-or-na [som skrev brev-et]

girl-PL-DET [REL wrote letter-DET

‘the girls who wrote the letter.’

However, looking at noun phrase word order, we have other candidates for “Dews-ish”. Swedish, like English and many other languages, has the ordering ADJ – NOUN- REL.CLAUSE (not surprisingly perhaps, since a relative clause is usually longer than an adjective, and there is a general preference in language to have longer, “heavier”, modifiers late in the clause). Dews-ish would then be a language with the ordering REL.CLAUSE – NOUN – ADJ. Surprisingly enough, there are many languages which could serve as Dews-ish in this respect. Basque is one, Burmese is another. For reasons of space, we will only show Basque here. Note that is so much of a mirror image that the Basque order can be derived almost entirely by reading the Swedish order backwards, word for word.

5a) den unga flicka-n [som har skrivit brev-et]

DET young girl-DET [REL has written letter-DET]

‘the young girl who has written the letter’

5b) [eskutitz-a idatzi du-en ] neska gazte-a

[letter-DET writtten has-REL] girl young-DET

‘the young girl who has written the letter’

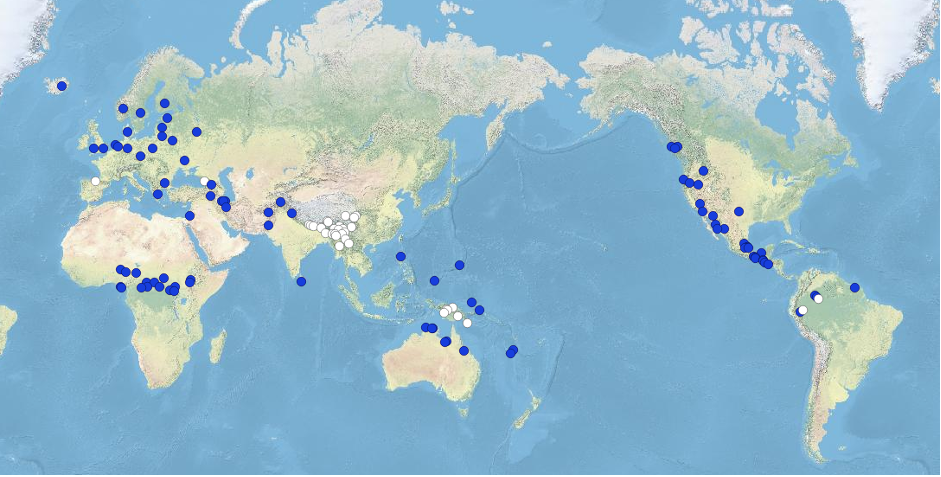

How many such languages there are is illustrated in the following map from World Atlas of Language Structure (wals.info). The blue languages are languages with the Swedish order, and the white languages are languages with the Dews-ish order (i.e. like Basque).

There is something exotically enticing about the idea that the mirror image of Swedish is spoken in the fishing villages and mountain farms of the Basque Country, where a pre-Indo-European people is steadfastedly preserving its way of life and its language.

In fact, there is something else to be said for this idea. In Swedish, as in English and in many other European languages, there is a gender distinction on 3rd person pronouns (hon = 3sFEM, han = 3sMASC), but none on 2nd person pronouns (du = 2SING, regardless of gender). Further, in Swedish as in English and many other European languages, gender is expressed on adjectives and other elements referring to the noun, but not on the verb (although Slavic languages like e.g. Russian, Polish and Czech are an exception here, and so is Arabic, as we saw before).

So Dews-ish could be a language where:

- i) gender is only expressed on the verb, not on a pronoun, noun or adjective or anywhere else; and

- ii) where gender is expressed in the 2nd person, never in the 3rd person.

And yes, Basque is such a language. Basque is usually described as entirely lacking gender. There is no grammatical gender on nouns, and there is no semantic gender on pronouns. The pronoun hura can mean either he or she. The word gizon ‘man’ inflects in every way exactly like the word emakume ‘woman’.

However, there is one, and only one, Basque construction which involves gender agreement. In this construction, it is the verb, and only the verb, that agrees in gender, but only with the person spoken to, regardless of whether this person is actually referred to in the sentence.

6a) Amak eskutitz-a idatzi du-k.

mother letter-DET written has-MASC

‘Mother has written the letter. (said to a man)’

6b) Amak eskutitz-a idatzi du-n.

mother letter-DET written has-FEM

‘Mother has written the letter. (said to a woman)’

This construction type is used in a special kind of familiar speech, similar to the contexts where French would use tu instead of vous, or German would use du instead of Sie. In fact, it is sometimes heard in political songs, a usage which clearly reflects a basic assumption that all men are brothers (as are all women, apparently, since it is always the masculine form that is used!).

7a) Ez gaitu-k lapurra-k ez eta zakurrak…

NEG 1PL.be-MASC thief-PL NEG and dog-PL

‘We are neither thieves not dogs…’

Is Basque, then, Dews-ish? We have seen some constructions where Basque does behave like Dews-ish. We have seen other constructions where Arabic behaves like Dews-ish. We could probably look at yet other constructions and discover that yet other languages are the mirror image of Swedish in that respect.

Does it even matter? In a sense, yes. Language typology is interested in what exists and what does not exist in human languages. Finding out what exists is easy enough by looking at actual languages. Finding out what does not exist can be a bit tricky, unless we imagine theoretical possibilities which we then do not actually seem to find in real languages. One simple thought experiment for identifying theoretical possibilities would be to take a random language, like Swedish, and try to imagine what the opposite of each construction type would be.

Does every construction type in Swedish actually have a mirror image? Perhaps, perhaps not. The answer to this question will be clear when we understand exactly what Kayne was referring to in his claim that “reverse German” does not exist, an issue which will be deferred to another post…

Comments