We have discussed some interesting food-related etymologies in our past blogposts, where we could see that the origin of food items often is reflected in the provenance of its name. This is far from always the case however, but this assumption is a common source of erroneous etymologies which sometimes become widespread in popular belief. One such example is the alternative etymology of the English word pumpkin, as it is claimed across the Internet to be originally from the Eastern Algonquian language Wampanoag (also known as Massachusett and Natick). Wampanoag was spoken in the area of the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, which was one of the earliest English colonies in the present United States of America, and Wampanoag was closely related to the neighbouring Narraganset from which the English borrowed the word asquutasquash that turned into the English word squash. Since both squash and pumpkins are members of the genus Cucurbita, which are all originally from the New World, it is tempting to wonder if the word pumpkin has an origin similar to that of squash, which I will prove to be incorrect below.

It is nevertheless claimed by e.g. the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, which is an effort to revitalize Wampanoag, that the English word pumpkin comes from the Wampanoag word pôhpukun with the meaning ‘grows forth round’. There are multiple problems with this claim and the first issue is that there are no historical attestations of the word pôhpukun, as it does not occur in John Eliot’s grammatical description from 1666, Cotton’s vocabulary from 1829 or Trumbull’s dictionary from 1903. The second issue is that the word pompion, which is the actual origin of pumpkin, is attested in English since the 16th century. The etymology of pompion is Middle French pompon, which in turn comes from Latin pepōn- or pepo ‘watermelon, gourd’ with the ultimate origin being Ancient Greek pépon ‘ripe, mellow’.

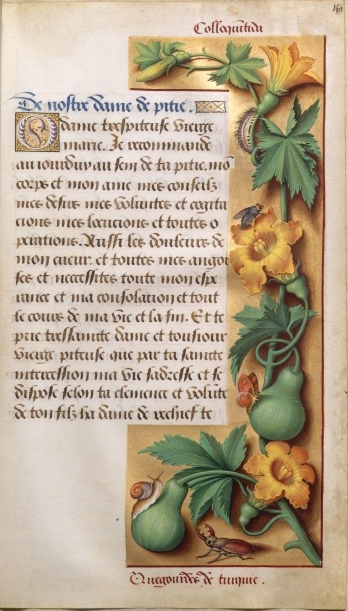

The word pompon is however not found in modern French, which makes it worth questioning if French can be the source. The first attestation of the English word pumpkin, where the now obsolete diminutive suffix –kin was added to pumpon, is from Nathanial Ward’s The simple cobler of Aggawam in America from 1647, which describes life in the English colonies, thus connecting the word pumpkin with Massachusetts. Why would a Middle French word for ‘melon’ or ‘gourd’ end up in colonial New England, particularly in reference to a New World crop? This might seem implausible at first glance, but pumpkins were already present in Europe around 1500, as pumpkins occur in the illustrations of Livre d’Heures d’Anne de Bretagne from 1508 (Wehner et al. 2020: 76). This shows a connection between Middle French and pumpkins, but not specifically to the word pompon however. This is instead something we find in Leonhart Fuchs’s De historia stirpium commentarii insignes which is a herbal published in 1549 describing various plants available at the time, where pumpkins are described as having the French names Citrulle (modern French citrouille ‘pumpkin’) or Pepon (Fuchs 1549: 664).

We furthermore have an early New World attestation in English of pumpion and pumpon in William Strachey’s The Historie of Travaile Into Virginia Britannia from sometime before 1612, but whose manuscripts were not formally published until more than two centuries later in 1849. Strachey writes e.g. that the indigenous cultures of Virginia ‘sowe their tobacco, pumpons, and a fruit like unto a musk million [muskmelon], but lesse and worse, which they call macock gourds’ (Strachey & Major 1849: 72). This is highly relevant as this was written before the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts was even founded in 1620. It is therefore apparent that the word pumpon was used by English settlers prior to the colonization of New England, thus showing that is impossible for Wampanoag to be the source of the word pumpkin. This stands in stark contrast with the other etymologies we have discussed in previous blogposts, as there is no doubt in this case that the proposed Wampanoag etymology is false. It might seem like a negative conclusion, but our investigation did on the other hand also clearly confirm the somewhat contra-intuitive origin of pumpkin as coming ultimately from Ancient Greek pépon via Latin and Middle French. Etymology is a fascinating field of research, as who would ever believe that an adjective from Ancient Greek would travel across oceans and through millennia to end up as the term of North America’s most beloved gourd.

References

Cotton, Josiah (1829). Vocabulary of the Massachusetts (or Natick) Indian Language. Cambridge, Massachusetts: E. W. Metcalf and Company.

Eliot, John (1666 [2001]). The Indian Grammar Begun: or An Essay to bring the Indian Language into Rules. Bedford, Massachusets: Applewood Books.

Fuchs, Leonhart (1549). De historia stirpium commentarii insignes. Lyon: Balthazar Arnoullet.

OED Online, Oxford University Press: https://www.oed.com/

Strachey, William & Major, R. H. (ed.) (1849). The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia. London: Hakluyt Society.

Trumbull, James Hammond (1903). Natick Dictionary. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of American Ethnology.

Wehner, Todd C., Naegele, Rachel P., Myers, James R., Dhillon, Narinder P. S., Crosby, Kevin. (2020). Cucurbits. 2nd edition. Wallingford, Oxfordshire: CABI.