In the Western world, we are increasingly being told to pay attention to what information sources the media use. We have recently seen the emergence of strange concepts such as fake news, alternative facts, and post-truth politics.

We’ve had to retroactively come up with ways of staying aware of this problem. But I can’t help thinking about the fact that, had our mainstream media been published in one of the numerous South American languages with evidential systems instead, we would already have a system in place for handling our information sources. Let me tell you why!

We’ll start with a brief detour into tense marking. In English—like in many other languages—every time you utter a sentence, you have to place the event you talk about on a timeline by conjugating the verb. Thus, we can say things like He drives to Denmark (present tense) and He drove to Denmark (past tense), but we cannot leave out this information: the grammar forces us to make a choice, and to make it explicit. English speakers automatically time-stamp their sentences in this way, without paying much attention to it. Not all languages have obligatory tense marking, though—In Mandarin Chinese, for example, the verb remains the same throughout the timeline. It’s possible to express information about time in Mandarin Chinese by using an adverb like ‘yesterday’ or ‘tomorrow’, but the important point is that it’s optional.

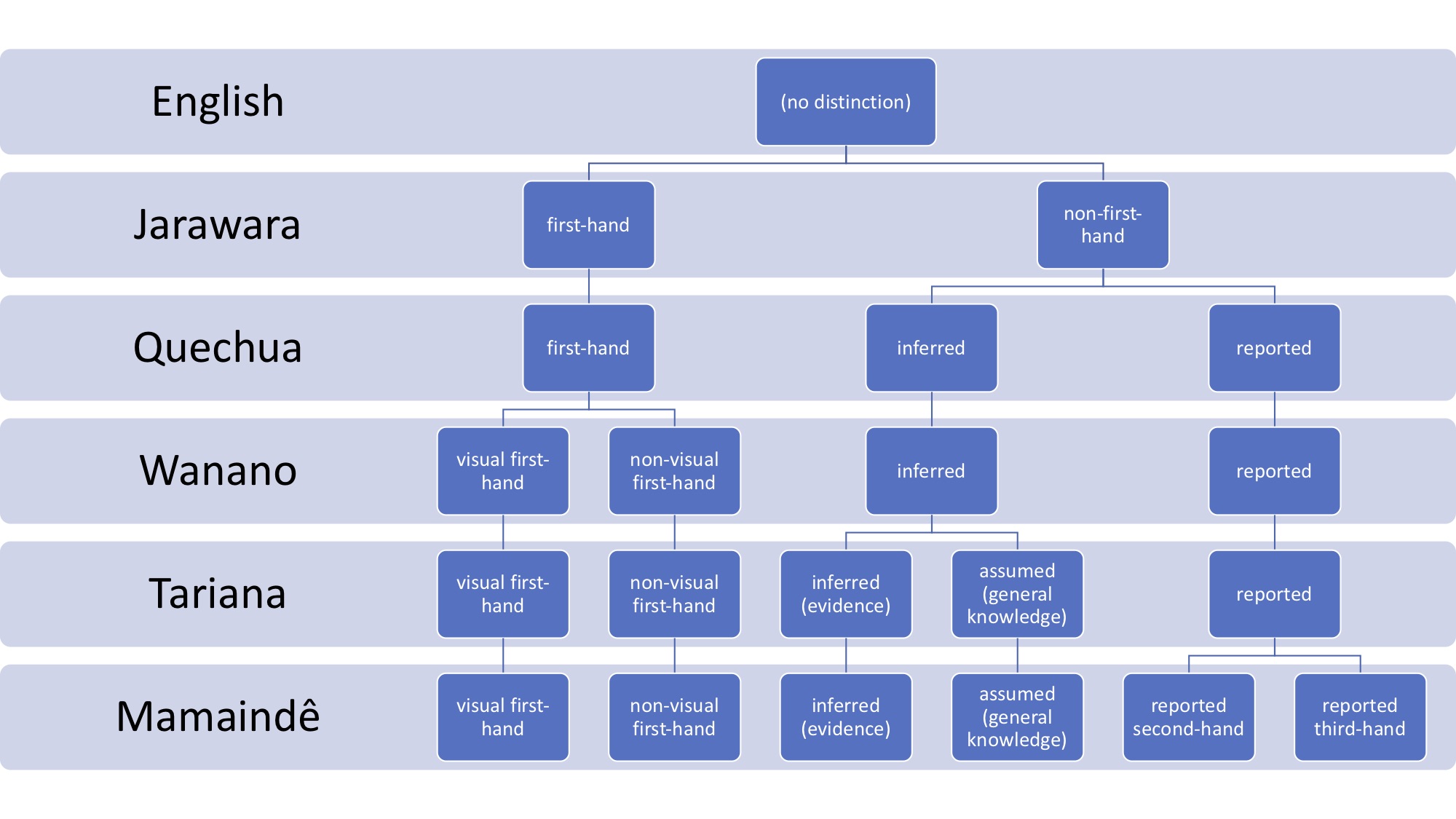

On to our main topic then: evidentiality. Similarly to the way English obligatorily includes information about time on the verb, many languages obligatorily indicate information sources in their grammar. How does this work? There are different kinds of systems, with different numbers of distinctions. Let’s have a look at a few different types.

1. Languages that make a two-way distinction in their evidential system often distinguish first-hand and non-first-hand information. An example of such a language is Jarawara from the Arawa family, spoken in Brazil. In the example below, the speaker marks the verb in each clause with –no ‘non-firsthand information’ and –hiri ‘first-hand information’, respectively, thus reporting whether or not they witnessed the event.

Wero kisa -me -no ka -me -hiri -ka Wero get.down-BACK-IMM.PST.NONFH.MASC be.in.motion-BACK-REC.PST.FH.MASC-DECL 'Wero got down from his hammock (which I didn't see), and went out (which I did see)'

2. Quechuan languages (spoken in the Andean region) make a three-way distinction of first-hand, inferred, and reported information.

trabaja -aña-m li-ku -n work.PURP.MOTION-now-DIR go-REFL-3.person 'He's gone to work (I saw him go)'

chay lika-n -nii juk -ta -chra -a lika-la that see -NMLZ-1.person other-ACC-INFER-TOP see-PST 'The witness must have seen someone else'

Ancha -p -shi wa'a-chi -nki wamla-a -ta too.much-GEN-REP cry -CAUS-2.person girl -1.person-ACC 'You make my daughter cry too much (they tell me)'

3. The East Tucanoan language Wanano, spoken in Brazil and Colombia, makes a four-way distinction: visual first-hand, non-visual first-hand (what you hear, smell or taste), inferred, and reported information. In first-hand information, Wanano thus makes a difference between sight and all other senses.

4. Tariana, an Arawak language from Brazil, makes a five-way distinction of visual first-hand, non-visual first-hand, inferred (from evidence), assumed (from general knowledge), and reported information.

Juse irida di -manika-ka José football 3PL-play -REC.PST.VIS.FH 'José played football (I saw it)'

Juse irida di -manika-mahka José football 3PL-play -REC.PST.NONVIS.FH 'José played football (I heard it)'

Juse irida di -manika-nihka José football 3PL-play -REC.PST.INFER 'José played football (I infer it from evidence – his football boots are missing)

Juse irida di -manika-sika José football 3PL-play -REC.PST.ASSUM 'José played football (we infer it from general knowledge – José usually plays football on Sundays)'

Juse irida di -manika-pidaka Jose football 3PL-play -REC.PST.REP 'Jose played football (we were told)'

5. Last but not least, the Nambiquara language Mamaindê (from Brazil) has one of the most complex evidential systems in the world. It has a six-way distinction of information source types: visual first-hand, non-visual first-hand, inferred, assumed (from general knowledge), reported second-hand, and reported third-hand information. Thus, the Mamaindê system is similar to that of Tariana, but it also distinguishes reported information into second- and third-hand.

We can summarize the evidential systems mentioned here in a table, where their increasing complexity becomes apparent.

To a speaker of a language without evidentials (like myself), these systems are fascinating, and it is hard to believe how speakers manage to keep track of how they came to acquire every single piece of information. To a speaker of a language with evidentials, however, it comes automatically—much like English speakers’ ability to automatically time-stamp their utterances.

The way an evidential system is used can nevertheless tell us interesting things about what is valued in the social context in which the language is spoken. In many of the South American languages that use evidentials, the choice of an evidential is intimately linked to a social code of taking responsibility for the truth of the utterance. Discrepancies in the ways people relate to the ‘truth’ can lead to cultural clashes, which become apparent through the use (or non-use) of evidentials. Aikhenvald (2012:268) gives the following illustrative example from a situation that, sadly, is all too common to indigenous South American communities: “A missionary comes and starts preaching. He states that Adam ate the apple in the Garden of Eden—and uses a visual or ‘personal knowledge’ evidential. An Aymara, a Tucano or a Tariana speaker, looks at him suspiciously: has he really seen it?”

On the other hand, some of the South American language communities that use evidentials may allow for utterances that the average English speaker wouldn’t accept as ‘truth’: for example, in Shipibo-Conibo, a shaman (who is perceived as omniscient) will use a ‘visual first-hand information’ evidential for retelling a dream or a vision—information that is, in a stricter sense, not visually verifiable (Aikhenvald 2012:269).

To be sure, languages without evidentials may specify the information source if they want to (just like Mandarin Chinese and other tenseless languages may optionally include information about time). In English, we can add adverbial and similar expressions such as ‘allegedly’, ‘…I heard’, ‘from what I can tell’, etc.—but, importantly, we don’t have to: the exclusion of the adverbial doesn’t make the sentence incomplete (compare Allegedly, he drove to Denmark and He drove to Denmark—there is a difference in meaning, but both are complete sentences). One may speculate that there is sometimes a certain degree of convenience (or perhaps an ideal of mutual trust?) in not having to present your source of information, and that the English speaking world prefers to keep it this way. In the end, it comes down to what the language community deems to be important enough to mention—or so I infer, based on internal conjecture.

Source: Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. (2012) The Languages of the Amazon (Chapter 9: How to know things: evidentials in Amazonia). Oxford University Press.