by Alex Garcia

There has been a growing global awareness of the loss of linguistic diversity since the end of the twentieth century. The number of projects in which a linguist travels to a rural community to document a language in danger of extinction has increased in the last two decades. Language documentation (LD), despite its twenty-five-year history, is still a relatively unknown discipline. Linguist Peter Austin points out that language documentation is supported by international academic journals, specialized conferences, and various training centres around the world (see here). Today, we’ll look at some of the methods and goals of this linguistics subfield.

The belongings of a field linguist provides some clues about what the job is like. The equipment typically includes a recorder and various types of microphones: one of the goals is to make recordings of a language for which documentation is scarce or non-existent. Such recordings are likely to be the only ones ever made, so it is crucial that they are of the highest possible quality. The equipment also includes a video camera, a computer, and various hard drives that store backups of valuable recordings. But this is not entirely new: before the emergence of language documentation, anthropologists and linguists were already travelling to remote communities to record and research languages. So what has actually changed with documentary linguistics?

According to one of the most influential documentation manuals, the main goal is to create a representative, multipurpose, and long-lasting record of a language. To achieve representativeness, the linguist collects samples of different types of communicative events of a community’s daily life. These events may include conversations, stories from the past, traditional tales, songs, and riddles may be included, as well as descriptions of local plants and animals, or instructions on how to weave, build a house, or fish. Some projects focus preserving community-specific register, such as the epic Hudhud chants of the Ifugao (Philippines), which can run for hours and are recounted by heart, or the instrumental and whistled speech registers used by the Gavião (Brazil), which imitate the language’s sounds.

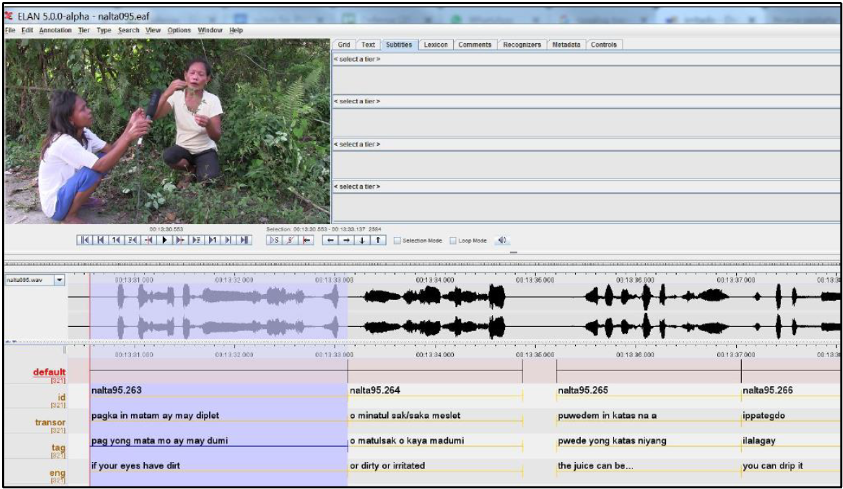

In terms of multifunctionality, the recordings must be able to be used by a variety of persons with a variety of intents and purposes. For this reason, priority is given to the collection and dissemination of primary data, i.e., unprocessed data, collected directly from the community of speakers. For this purpose, a substantial part of the fieldwork time is dedicated to annotating recordings, a process in which the constant supervision of a native speaker is needed. The most basic form of annotation entails segmenting each recording into sentences and adding a transcription and a translation into English. Such annotation allows users without prior knowledge of the language to understand the content of the recordings, and also to research and cite them. The set of recordings collected and annotated by a linguist is referred to as an “annotated collection” or “language documentation corpus.”

Back at home, the linguist uses the collection to conduct a systematic investigation of the language to create a grammatical description. Simultaneously, the collection is prepared to be uploaded into one of the DELAMAN archives, a network dedicated to primary data and endangered languages. For example, archives like ELAR (Germany), TLA (Netherlands), or RWAAI (Lund University), play a key role in language documentation: they promote access to the collections, and more importantly, they assure their long-term preservation so that future users can access them. Note that if we browse the catalogues in these archives, it may seem as if a lot of documentation has been completed, but there is a lot more to do! There are many languages that need documentation, and nowadays, previously unknown languages are still being identified, as with Jedek, an Austrosiatic language spoken in Northern Peninsular Malaysia.

On the other hand, many languages for which an annotated collection has been produced have only been partially investigated, given that many projects are confined to producing a grammar and a lexicon of the language. Linguist Lawren Gawne encourages other linguists to work with her collection, in a guide to the Syuba language documentation corpus (Nepal), and outlines which aspects of language are left to be researched. She also specifies which parts of the collection can be used by anthropologists or historians, and also states that the material is of sufficient quality for filmmakers to exploit, as demonstrated in this showreel Finally, Gawne emphasises that language speakers are the most significant users of her collection. The annotated collection, along with the grammar, can be used to create instructional materials that could aid in the language’s transmission. Furthermore, future generations of the Syuba community will be able to view the video catalogue of their ancestors at their leisure, thanks to the role of language archives.

Language documentation has had a favourable impact on different fields of knowledge since its inception. For example, a master’s or PhD student could be able to use an LD corpus to write a dissertation on a specific language. It also enables academics from different locations or times to access an annotated collection and verify or refine linguistic analyses. The latter point is not only beneficial, but vital: despite the fact that each language represents a vast universe of knowledges, most languages are documented by a single linguist—or a small team for the lucky ones. Consider the number of linguists working on English or French, for example. In comparison, how much could a single individual accomplish? Here is one of the most important contributions of language documentation: it intends to promote and aid different kinds of users in navigating through such universes, whereas in the past, linguistic data was often collected for a specific reason and was rarely shared.

References

Austin, P. (2015). Language documentation 20 years on. In M. Pütz & L. Filipovic (Eds.), Endangerment of languages across the planet (Amsterdam:, pp. 147–170).

Gawne, L. (2018). A Guide to the Syuba (Kagate) Language Documentation Corpus. Language Documentation & Conservation, 12, 204–234.

Gippert, J., Himmelmann, N. P., & Mosel, U. (Eds.). (2006). Essentials of Language Documentation. Mouton de Gruyter.

lldf

Great blog post, Alex!