by Arthur Holmer

Ask a speaker of English what the most salient fact about English is, and it is very unlikely that the answer will be “do-support”. Similarly, we would be surprised if we heard a Gael bragging about initial mutation, or a Finn about consonant gradation, or indeed a German about verb-second word order. These phenomena, insofar as speakers are in any way consciously aware of them, are not considered to be anything special, except perhaps that they are possible sources of difficulty for anyone learning the language.

Not so for Basque ergativity. Ask any speaker of Basque for an important fact about Basque, and they will (in addition to the obvious fact that Basque is a language isolate, i.e. that it has no known relatives) in all probability mention ergativity, that is to say the fact that the subject of a transitive verb like eat gets a special type of case-marking (the -k suffix in the following example), whereas subjects of intransitive verbs like come and go do not. The subject of a verb like come or go behaves like an object, and gets no case-ending.

Sagua etorri zen. mouse come AUX ‘The mouse arrived.’ Katua-k sagua jan zuen. cat-ERG mouse eat AUX ‘The cat ate the mouse.’

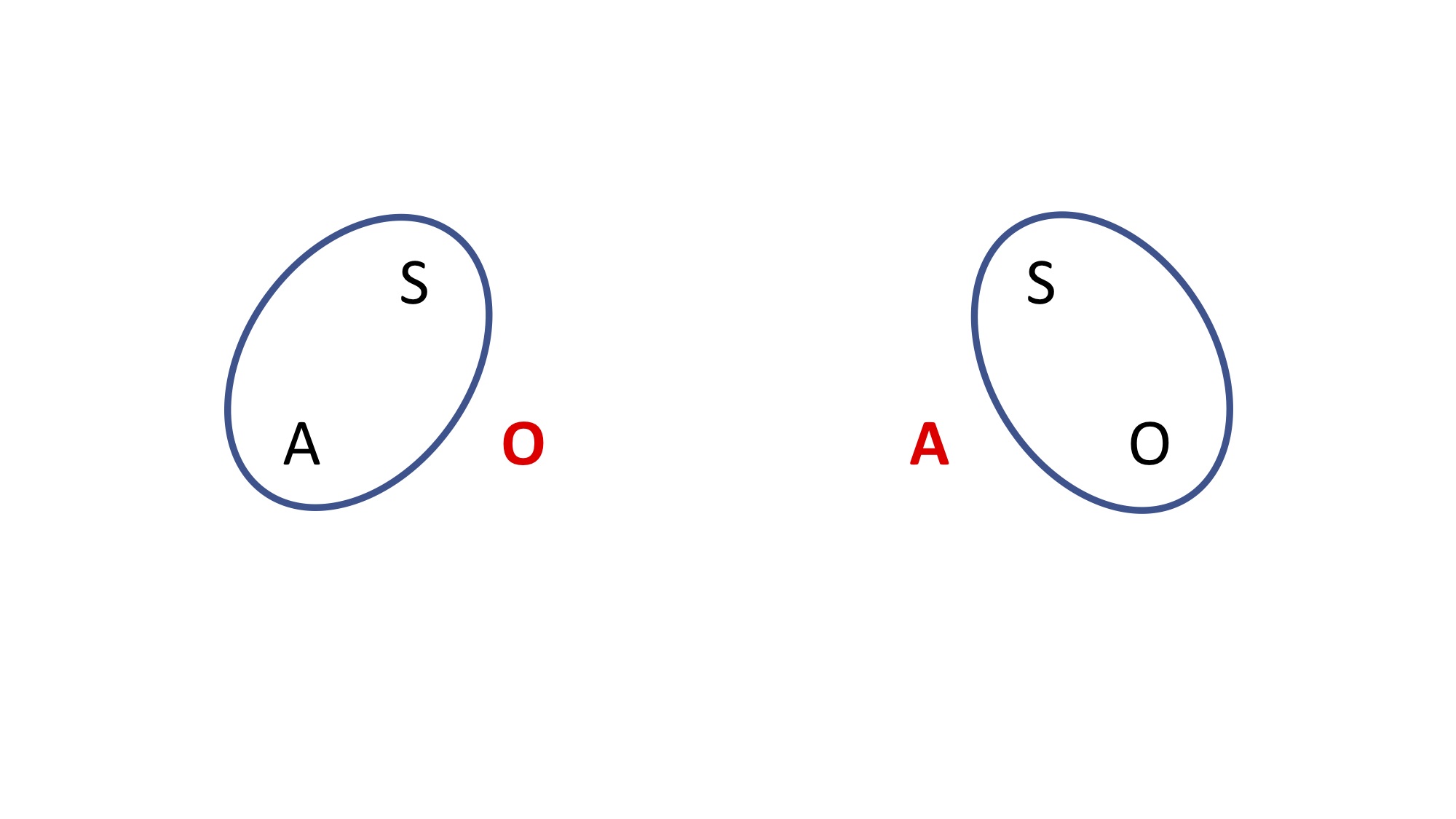

Ergativity is often described in terms of three separate roles, usually defined by the abbreviations A, S and O:

A (=”agent”) subject of transitive verbs like hit or see

S subject of intranstive verbs like come or go

O objects of transitive verbs like hit or see

In a language like English, it seems so obvious that A and S behave identically, that we don’t even think of these are separate roles. For us, they are simply the “subject”. For a speaker of an ergative language like Basque, A is the odd one out, the one which gets ergative case, while S and O behave identically.

Why speakers of Basque are consciously aware of ergativity is presumably because they notice how Spanish or French are different from Basque, and almost certainly also because language is such an integral part of Basque identity.

Unfortunately, however, the claims of Basque ergativity are a bit exaggerated. Basque is not nearly as ergative as the Basques themselves would like to believe. Basque (at least the standard language, based on western dialects) is more aptly described as an “active” language, which although it does lend a flavour of dynamic youthfulness, is nowhere near as cool as being an ergative language.

Being an active language means that the subjects of some intransitive verbs (such as dance and sing) end up in ergative, and the subjects of other intransitive verbs (such as come and go) do not.

Haurra-k abestu zuen. Haurra joan zen. child-ERG sing AUX child go AUX ‘The child sang.’ ‘The child left.’

Nevertheless, in a simplified classification (shared by Basque speakers and most linguists alike), Basque is an ergative language, with no known relatives.

Ask a Georgian (of Tbilisi, not of Atlanta!) if they know anything about Basque, and surprisingly enough, they probably will, they will probably also tell you that it is not an isolate, since it is in fact related to Georgian! And one of the pieces of evidence you may be given is that both languages share the feature of ergativity.

Now, Georgian is probably an even poorer candidate than Basque for pure ergativity. Not only is Georgian active, like Basque, but it also has a mixed system (called “split ergativity”), whereby it behaves like Basque in the past tense, but like English in the present tense. Even this is in fact a gross oversimplification, as the Georgian system is even more complex, and actually also much more exciting than simple ergativity. But it does raise the question of whether pure ergativity does exist, and if so, where?

What is then this elusive pure ergativity? It would imply that S and O always behave identically, in every respect, in the same sense that S and A always behave identically in English, or Swedish, or Spanish.

Does it indeed matter if pure ergativity exists? Perhaps not. But it is sometimes pointed out that language and thought may be interconnected. If this is the case, it becomes an interesting (if somewhat speculative) question whether or not a purely ergative system might not in some way be reflected in the world view of the speakers. If a transitive action always treats the patient/object as the least marked and default participant of the action, in other words, if the language consistently views an action from the point of view of the patient/object, rather than of the agent, could this somehow be mirrored in how the speakers view their world? This is an intriguing question, but it cannot reasonably be tested on either Basque or Georgian. Instead, access to a maximally ergative language would be required.

In ergative language after ergative language, from Burushaski to Chukchi to Greenlandic, we inevitably find some feature which groups A and S together. In most languages, reflexives (like myself) must refer to A or S. Some kinds of adverbs (like deliberately) must refer to A or S. In almost all ergative languages, an omitted subject in a clause must refer to A or S of the preceding clause, just like in English. The following Basque example is adapted from Ortiz de Urbina 1989.

Ama-k semea eskola-n utzi, eta Ø klasera joan zen.

mother-ERG son school-in leave and class-to go AUX

‘Mother left her son in school and (she / he) went to class.’However, in Dyirbal, a moribund language spoken by a handful of people south of Cairns in the state of Queensland, in Australia, even this feature groups S and O together.

Nguma yabu-nggu buran, Ø banaganyu.

father mother-ERG see return

‘Mother saw father and (he (!) / she) returned.’ (Dixon 1994:155)This phenomenon is called syntactic ergativity, meaning that even sentence structure treats S and O in the same way. This can be recognized easily in examples where two main clauses are juxtaposed, as well as in other more complex constructions.

Unfortunately, even Dyirbal is not a candidate for pure ergativity either, since pronouns still behave like they do in English (S and A have one case form, while O has another), cf. examples from Dixon (1972).

Ngaja baningu. Nginda baningu. 1SG (S) arrive 2SG (S) arrive ‘I came here.’ ‘You came here.’ Ngaja ngin-una buran. 1SG (A) 2SG-ACC (O) see ‘I saw you.’

There seem to be a few languages in Queensland (among others Yidiñ, Kalkatungu, Bandjalang and Yalarnnga) which share the syntactic ergativity found in Dyirbal. Unfortunately, most of these also behave like Dyirbal in that pronouns group S and A together, as in English. In Kalkatungu, full pronouns do group S and O together against A, but there is a separate system of bound (short, unemphasized) pronouns that still behave like in Dyirbal.

It is only in one single of these languages, Yalarnnga, that purpose constructions show that the language is syntactically ergative (like Dyirbal), while the pronoun system, unlike Dyirbal, is also fully ergative (there are no bound pronouns that go the other way).

The ergative case-marking of the pronouns is clear from the following example, where the transitive verb hear has the subject ngathu, while the intransitive verb go has the subject ngiya.

Kuntu nhawa nga-thu mangka-mu... not 2SG 1SG-ERG hear-PAST ‘I didn't hear you...’ (Breen & Blake 2007:27) Kuyirri nhina-mu, ngiya ngani-mu. boy be-PAST 1SG go-PAST ‘When I was a boy, I went.’ (Breen & Blake 2007:67)

To illustrate syntactic ergativity is a little bit more tricky. One way of testing it is the behaviour of purpose clauses (which express the purpose for which another action is performed). In a purpose clause, if the omitted element is to be understood as A, the verb must be specially marked with a marker –li– (“antipassive”) which serves to tell us that the omitted element is neither S nor O.

Ngani-mi ngiya [ Ø manhi-wu miya-li-ntjata ]. go-FUT 1SG food-DAT get-ANTIPAS-PURP ‘I’ll go and [Ø get food].’ (Breen & Blake 2007:59)

There are two contexts where the antipassive marker –li– does not occur. One is when the verb in the purpose clause is intransitive (like sit in the following example), so the omitted element must be S.

Ngiya laa-kanu ngana, [ Ø wayi-ngali-mpa nhina-ntjata ]. 1SG now-again go.NONFUT that-PL-ALL sit-PURP ‘I’m going now too, to be with those others.’ (Breen & Blake 2007:64)

If the verb is transitive, like wash, and the antipassive marker –li– does not occur, the omitted element is necessarily understood as referring to the object (O) of the action wash (in other words, the purpose clause can readily be translated as a passive).

Nga-thu tjaa ngapa-nha ngani-ntjata marnu-yantja-mpa [ Ø karri-ntjata ]. 1SG-ERG this tell-PAST go-PURP mother-POSS-ALL wash-PURP ‘I told him to go to his mother and get washed.’ (Breen & Blake 2007:60)

In Yalarnnga, purpose clauses single out the situation where A is omitted as the special case which must be marked on the verb. If the omitted referent is S or O, this special marking does not occur. As far as can be seen, Yalarnnga syntax treats S and O in one way, and A in another way, and there appears to be no construction which treats S and A alike.

This might not look all that striking, but this is what pure unadulterated ergativity looks like. There is not a lot of it around. In fact, Yalarnnga may be the only language in the world which consistently and exceptionlessly groups S with O to the exclusion of A, in every construction in the language. In other words, the exact mirror image of a language like English, Russian or Latin.

So if we want to investigate the properties of possibly the single currently attested purely ergative language in the world, the ultimate apex of ergativity, we should be prepared to travel to Dajarra, about 1000 km inland, more or less half-way between Cairns and Alice Springs.

Or we should have been. Sadly, the last native speaker of Yalarnnga died in 1978.

Postscript, caveat and a word of comfort

While Yalarnnga appears to be the only purely ergative language in Australia, at least of which we have enough data, (some degree of) syntactic ergativity has been reported at least in two other languages, Päri, spoken by over 20.000 people in South Sudan, and Nadëb, spoken by a few hundred people in the upper reaches of the Amazon, in Brazil. Whether or not these are purely and consistently ergative remains to be seen.

References

Breen, Gavan & Blake, Barry. 2007. The grammar of Yalarnnga. A language of western Queensland. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1972. The Dyirbal language of North Queensland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1994. Ergativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ortiz de Urbina, Jon. 1989. Parameters in the grammar of Basque. A GB approach to Basque syntax. Dordrecht: Foris.