When I was a child in the mid-90’s – before communication over the internet was widespread – I used to be pen pals with some of my Finnish cousins and friends. I sometimes received letters addressed to “Sandra Gronhamn”, which is a misspelling of my Swedish last name Cronhamn, pronounced with an initial [k]-sound. I also noticed that my Finnish relatives tended to not just spell, but also pronounce, our last name with a [g]. It wasn’t until I started studying linguistics many years later that I understood what was going on.

What my Finnish relatives were doing is called hypercorrection in technical terms. It’s a sociolinguistic phenomenon where a linguistic pattern is overapplied due to unfamiliarity with its distribution in the language or linguistic register in question. Hypercorrection should not be written off as errors or incompetence, however – it’s a very interesting phenomenon which actually stems from a quite deep awareness (even if subconscious) about differences in phonological and grammatical patterns. Hypercorrection also sheds light on the intricate processes and effects of language contact.

Hypercorrection can take place between separate languages, as in the example above about Finnish speakers pronouncing or spelling a Swedish name. In fact, this example is part of a broader pattern. Finnish lacks so-called voiced stops (the sounds [b, d, g]) in native vocabulary, and in early loanwords from Germanic languages, these were replaced by their voiceless counterparts [p, t, k]: Swedish bädd ‘bed’ was borrowed as peti, and gata ‘street’ as katu. Slowly but surely, however, the voiced stops sneaked their way in to the Finnish phonological system through long-standing language contact. [b] is now its own phoneme, since it contrasts with [p] in minimal pairs like baletti ‘ballet’ and paletti ‘palette’.

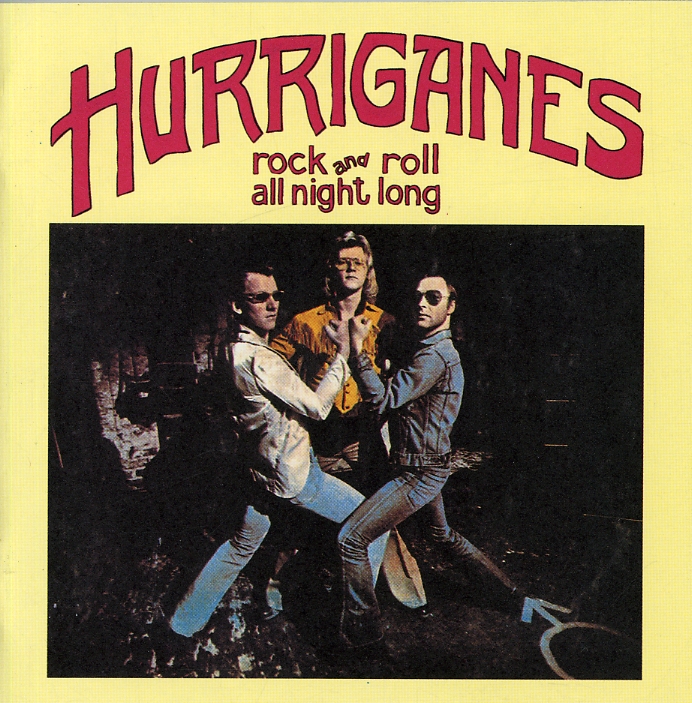

This provides the background to Finnish hypercorrection of voiced stops in languages like Swedish and English (which they are all more or less familiar with since they learn both in school). They become aware of the fact that [p], [t] or [k] in a Finnish loanword often corresponds to [b], [d] and [g], and since this sounds less Finnish, they sometimes overapply this pattern – even in cases where [p], [t] and [k] actually correspond to [p], [t] and [k]. This happens not only in Cronhamn > Gronhamn, but also in e.g. biisi ‘song’, which is from English piece. Another example is the Finnish 70’s rock back named Hurric… no, sorry, Hurriganes.

Swedish speakers also engage in hypercorrection, for instance in the pronunciation of some French loanwords. Most Swedes have at least a vague acquaintance with French pronunciation, for example that they tend not to pronounce consonants towards the end of a word. This assumption, which is only partially true, explains the fact that entrecôte is pronounced without the final [t] in Swedish, despite the fact that the [t] is pronounced in French. To Swedish speakers, it simply sounds more French to skip it.

The examples we’ve seen so far have all had to do with phonology, i.e. sound patterns. But hypercorrection can also target grammar. For example, English speakers tend to overgeneralize certain plural forms which are borrowed from classical languages. Sometimes, octopuses (in the plural) are referred to as octopi, assuming that it is a Latin word following the same pattern as e.g. alumnus–alumni. Octopus is indeed borrowed from Latin, but it is of Greek origin, and the Latin plural form is octōpodēs.

Hypercorrection does not need to operate across language boundaries – it also commonly occurs between different registers of the same language. For instance, speakers of what is perceived as a less prestigious dialect may hypercorrect certain patterns in their own speech to something which is associated with a more prestigious variant. An example from English is the pronunciation of umbrella as umbrellow, in analogy with fellow, which is perceived as a more standard pronunciation than colloquial fella.

Why do we hypercorrect? Quite simply, we like to generalize things, and if for instance a Swedish speaker applies the rule ‘do not pronounce consonants towards the end of a word’ to French pronunciation, they may produce correct pronunciations 99% of the time. As such, it is a viable strategy. Hypercorrections constitute the small portion of unsuccessful attempts at applying a rule – however, without them, we may not have noticed the rule in the first place.