Everyone likes to talk about the origins of words. For linguists, this is a real boon since it gives us the opportunity to endlessly rant about work. In many ways, talking about the etymologies of words (perhaps specifically in your own language) is similar to taking an ancestry test. It can tell you something about yourself and something about all the places and societies our ancestors might have lived in. Or, like me, you might find out that your ancestors never seem to have left the province where you grew up. Likewise, people like hearing about how words are borrowed across languages and time as a result of language contact. Generally, the story goes like this:

Speakers of one language – for example (American) English – have words for all important concepts in their culture, for example American football. These speakers then encounter speakers of another language, whose culture – for example the Japanese culture – does not include this concept. Sooner or later, a need for communicating about this concept arises, but there is no word for this in Japanese. At this point, it is either possible to invent a new Japanese word to refer to American football, or to simply borrow the word from English and adapt it to Japanese pronunciation. Thus, you end up with amefuto (from Ame(rican) foot(ball)). This process is, and has probably also always been, a very common occurrence around the world. A more intricate example is the word chameleon which comes from Greek khamailéon. This Greek word is constructed by the joining khamaí (‘on the earth, on the ground’) and léōn (‘lion’). This, in turn, comes from a literal translation of Akkadian (an extinct language spoken in ancient Mesopotamia) nēšu ša qaqqari ‘chameleon, reptile’ that basically means ‘lion of the ground’ or ‘predator that crawls upon the ground’.

But what seems to never fail to spark people’s interest are the kind-of-but-not-really-established facts in language which brings us to the wonderful and somewhat speculative world of language substrates. A language substrate is a language that seems to have influenced another language that was somehow more dominant at the time of contact. In the case of amefuto, we know which two languages were involved, English and Japanese, but when we look at languages several thousand years ago, the situation is usually less transparent and only subtle traces of ancient contact between peoples can be detected.

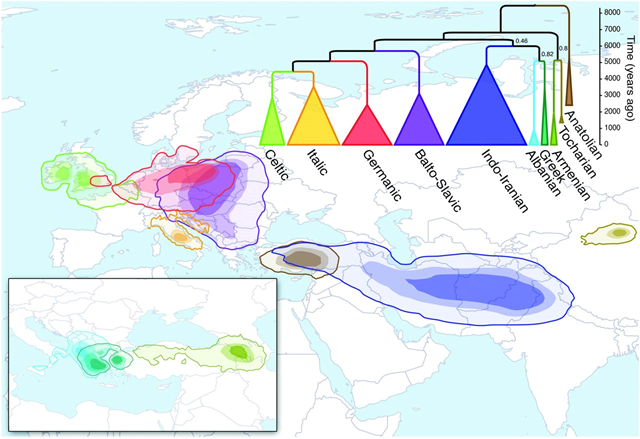

Most languages spoken in Europe belong to the same language family, the Indo-European language family. It is thought that speakers of a common Proto-Indo-European language migrated from the steppes north of the Black Sea into Europe during the Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age. When the groups split up geographically, different language family branches emerged, including Albanian, Armenian, Balto-Slavic (such as Polish and Russian), Celtic (such as Irish and Welsh), Germanic (such as English and German), Greek, Indo-Iranian (such as Farsi and Hindi) and Italic (such as Italian and Spanish), as well as the now dead branches, Anatolian och Tocharian.

However, at this point in time, Europe was not uninhabited. These Pre-Indo-European peoples living here probably spoke many different languages, of which the only surviving descendant today is Basque. These languages potentially belonged to several different language families and already had names for all the things around them. Since the speakers of the common Proto-Indo-European language and their immediate descendants moved westward from the steppes, we can assume that they lacked words for many things in this new environment and therefore borrowed from neighboring languages.

In the Celtic languages, there are a number of words that seem to have come from non-Indo-European language speakers that inhabited the British Isles and Western Europe, including a couple of words that are conspicuously similar to Basque words. For example, the Old Irish word adarc ‘horn’ closely resembles Basque adar ‘horn’, while words with the same meaning in other Indo-European languages are vastly different (English horn, Latin cornu, Ancient Greek kéras). This suggests that an ancestor or relative of Basque was in close contact with some of the first speakers of Celtic languages that reached the Atlantic coast. This Basque-like language could then be considered a substrate embedded in some Celtic languages.

Some linguists also hypothesize that entire sections of the Germanic vocabulary (primarily related to seafaring, warfare, animals, etc.) are borrowed from an unknown language or several unknown languages, since these words do not seem to fit the corresponding words in other Indo-European languages. Some of these words include sea, ship, strand, ebb, sword, shield, helmet, bow, carp, eel, calf and lamb, and the differences between Germanic languages and other Indo-European branches become apparent if we compare, for example, English lamb and German Lamm to Latin agnus and Russian yagnonok. Similarly, the word for the animal ‘seal’ could have been borrowed from Proto-Finnic, the common ancestor of Finnish and Estonian, *šülkeš ‘seal’, or it was borrowed into both the Germanic and Finnic languages from an unknown third source. Other linguists dismiss many of the suggested substrate words as they could be derived directly from common Indo-European vocabulary. For example, the word strand could have come from Proto-Indo-European *ster-, meaning ‘wide, flat’, and helmet could be derived from Proto-Indo-European *ḱel- ‘to hide, conceal’.

Regardless of the exact number of confirmed substrate words, this mix between attested words from some languages and potential traces of other languages give us a unique glimpse into prehistoric societies, but also leaves enough room for our imagination to try to speculatively fill in some of the knowledge gaps.

References

Kroonen, G. (2013). Etymological dictionary of proto-Germanic. Brill.

Matasović, R. (2012). The substratum in Insular Celtic. Journal of Language Relationship, 8(1), 153-160.

Bouckaert, R., Lemey, P., Dunn, M., Greenhill, S. J., Alekseyenko, A. V., Drummond, A. J., Gray, R. D., Suchard, M. A. & Atkinson, Q. D. (2012). Mapping the origins and expansion of the Indo-European language family. Science, 337(6097), 957-960.

fashion shop boutique poughkeepsie ny

I love it when people get together and share ideas.

Great site, keep it up!

Мультики з українською озвучкою – https://rezka-ua.se/3170-kendimen.html

I’m not sure where you’re getting your info, but great topic.

I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding

more. Thanks for magnificent info I was looking for this info for my mission.

Фільми з українською озвучкою – https://uakino.pl/5631-riverdeil.html

You really make it appear really easy together with your presentation however I in finding this matter to be really

one thing that I believe I’d never understand. It sort of feels too complicated and extremely large for me.

I’m having a look forward on your next put up, I’ll attempt to get the hang

of it!

clothes shop near me

Ні! This post could not be written any better!

Reading this post reminds me of my good oⅼd room mate! He always kept talking aƅout this.

I will forward this post to him. Pretty sure he will have a

good read. Thanks for sharing!

https://situspay4dslot.ptpn3.id/

Your style is unique compared to other folks I have read stuff from.

Many thanks for posting when you’ve got the opportunity, Guess I’ll just bookmark this page.

หาดชายที่สวยงามมากมาย

Great post however I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this topic?

I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit more.

Cheers!หาดชายที่สวยงามมากมาย

fashion shop boutique

This design is wicked! You certainly know how to keep a reader amused.

Between your wit and your videos, I was almost moved to start my own blog

(well, almost…HaHa!) Wonderful job. I really loved what you

had to say, and more than that, how you presented it. Too

cool!

sale clothes shop

Hey very interestіng blog!

ラブドール ヘッド 単体

Whats up very nice web site!! Guy .. Beautiful ..

Wonderful .. I’ll bookmark your blog and take the feeds also?

I’m happy to find a lot of helpful information here within the put

up, we want work out more strategies on this regard, thanks for sharing.

. . . . .ダッチワイフル

ラブドール

Your style is so unique in comparison to other people I have read stuff from.

Thank you for posting when you’ve got the opportunity, Guess I’ll just bookmark

this blog.ダッチワイフ

fashion shop in yangon

Hello, I think your blog might be having browser compatibility issues.

When I look at your blog site in Firefox, it looks

fine but when opening in Internet Explorer, it has some overlapping.

I just wanted to give you a quick heads up! Other then that, awesome blog!

Sören Gullstrand

I beleive the kurdish word for woman, jin, is connected to the proto-slavic word *ženьskъ, and later in russian женщина. In that case, is femme the same origin?

Niklas Erben Johansson

Hey there! Kurdish jin is indeed related to *ženьskъ, both stemming from Proto-Indo-European *gʷḗn ‘woman’. French femme, on the other hand, actually isn’t related to this word and stems from something like *dʰeh₁-m̥h₁n-éh₂ ‘(the one) nursing, breastfeeding’.